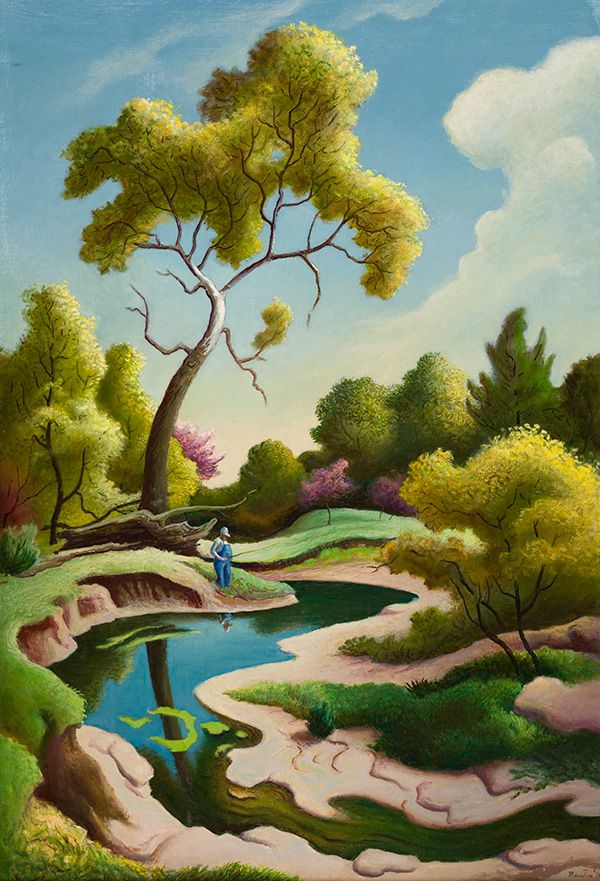

At the center of Thomas Hart Benton’s Clay County Farm, a lone farmer in blue overalls casts his fishing line into the still waters of a pond. All around him, the land seems alive with rolling hills, outstretched trees, and swirling clouds, each echoing one another in rhythmic, curving shapes.

The painting demonstrates Benton’s hallmark style, with bold colors and exaggerated shapes, used to elevate rural American life.

Painted in 1971, late in his career and against the backdrop of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement, Clay County Farm shows Benton’s devotion to a romanticized vision of America where labor and land defined the cycles of life.

Benton was a central figure of American Regionalism, an art movement of the 1920s and ’30s that rejected both urban modernism and European influence. Alongside Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry, they formed the so-called “Regionalist Triumvirate,” celebrated for their accessible depictions of small towns and farms. Yet Benton’s work was polarizing, praised for its populist appeal, but also criticized for his outright dismissal of abstraction and for idealizing rural life and conservative values.

Born in Missouri in 1889 into a prominent political family, Benton defied expectations by pursuing art rather than politics. He studied in Chicago and Paris, absorbing modernist approaches before turning back to the American Midwest with a more traditional focus.

Benton traveled extensively throughout the country, capturing workers, landscapes, and communities, including Arkansas, where he painted the Buffalo River and Ozark hills. These travels deepened his connection to the land and people, which became the heart of his Regionalist style.

As art historian Matthew Baigell observed, “Benton’s overwhelming love of America found its true outlet—in the streams, hills, and the mountains of the country, populated by people unsuspectingly living out their time, quietly enjoying themselves, living easily on the land, celebrating nothing more than their existence.”

By the time Benton painted Clay County Farm, he was nearing the end of his life. Once at the center of American art, he had become increasingly isolated, his work seen by some as out of step with the times. Yet, through the isolated farmer enveloped by the landscape, Benton reflects his own lifelong belief: that

humanity, labor, and nature are inseparable, bound together in a harmony that is enduring and, for him, divine.